Because I’m inspired by WWIII87 doing something similar and since I don’t think I’ll ever touch on the topic in any proper All Union successor, here it goes. It was in my mind, now it’s not. Enjoy.

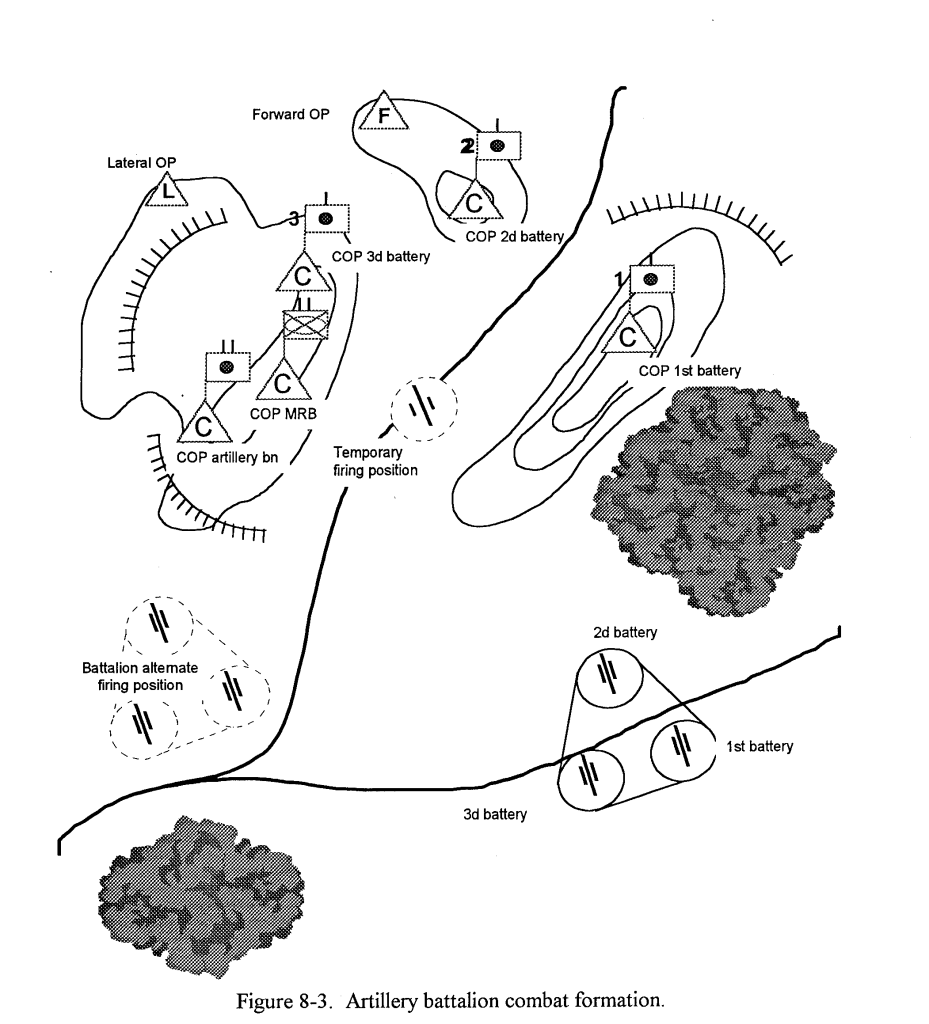

Like with most wars since 1900, if not since the invention of gunpowder, the Soviet-Romanian War in All Union was won by artillery. While the Soviets had far more and far more advanced tube pieces, fire control was a lot more varied on both sides.

Top Tier

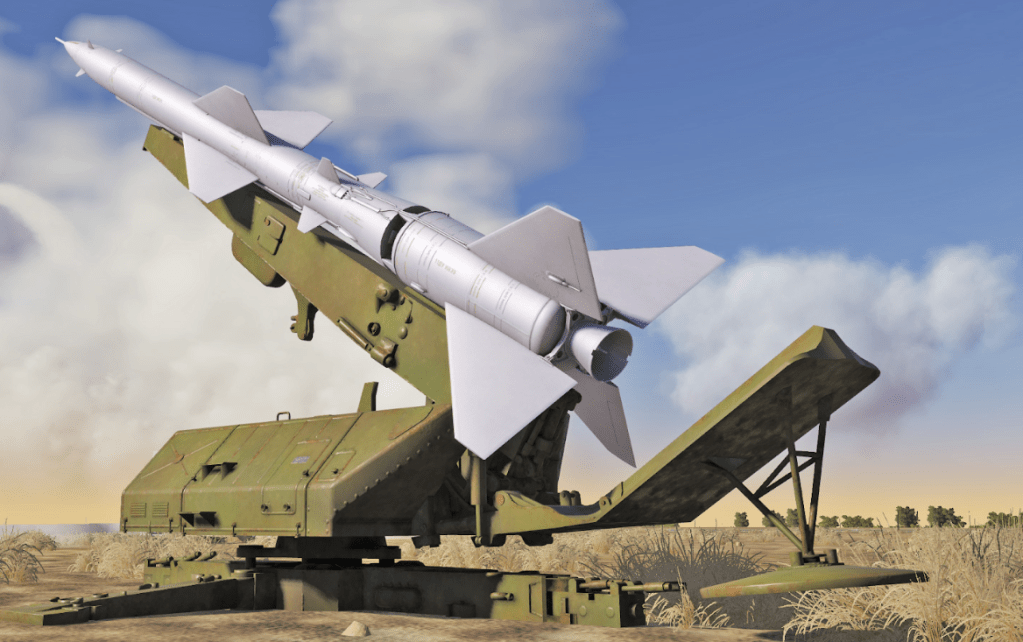

The top tier of fire control lay in the front level assets and units in the mobile corps, from battalion to corps itself. These contained most of the what the “recon strike complex” needed to succeed and did. Drone (and advanced non-drone) spotters, high performance datalinks, widespread designators for smart munitions, and advanced digital computers, all of it was present and used to great success. Perhaps the biggest air/artillery feat was the near-destruction of the Romanian 6th Tank Division before a single bullet was used in direct fire. The Romanians and allied Bulgarians had nothing like it. This was what caused a gigantic amount of alarm in the US and western militaries…

…although calmer heads pointed out that while still dangerous in the extreme, the Romanians had very little ability to disrupt the system.

Medium Tier

The medium tier was done by most regular Soviet units in the traditional division/army formation and the best Bulgarian/Romanian units. This involved fire control computers and other technological advantages, but still showed signs of stiffness and weakness in comparison to their upper tier (not the same as ineffectiveness, of course).

Low Tier

The low tier was largely manual and familiar to anyone in World War II, and was conducted by the bulk of Bulgarian and Romanian units, as well as a few low-category Soviet units mobilized for the war. There were many reasons why the southern front was less open and why the Romanian defense there was more effective: Units of mobilized Bulgarians instead of high-tech mobile brigades, the use of the Danube and more defensive lines, the proximity of Bucharest meaning that there was a “back to the wall” attitude, and many of the regime’s most loyal and stubborn units being deployed there prewar, possibly for political reasons.

Yet one has to be better C3I on the Romanian side (a large fortified area meant they could use field telephones and other such rugged measures far better) and worse such measures on the Soviet/Bulgarian side (especially as they had to go on the offensive). Which in turn made fire control better/worse.