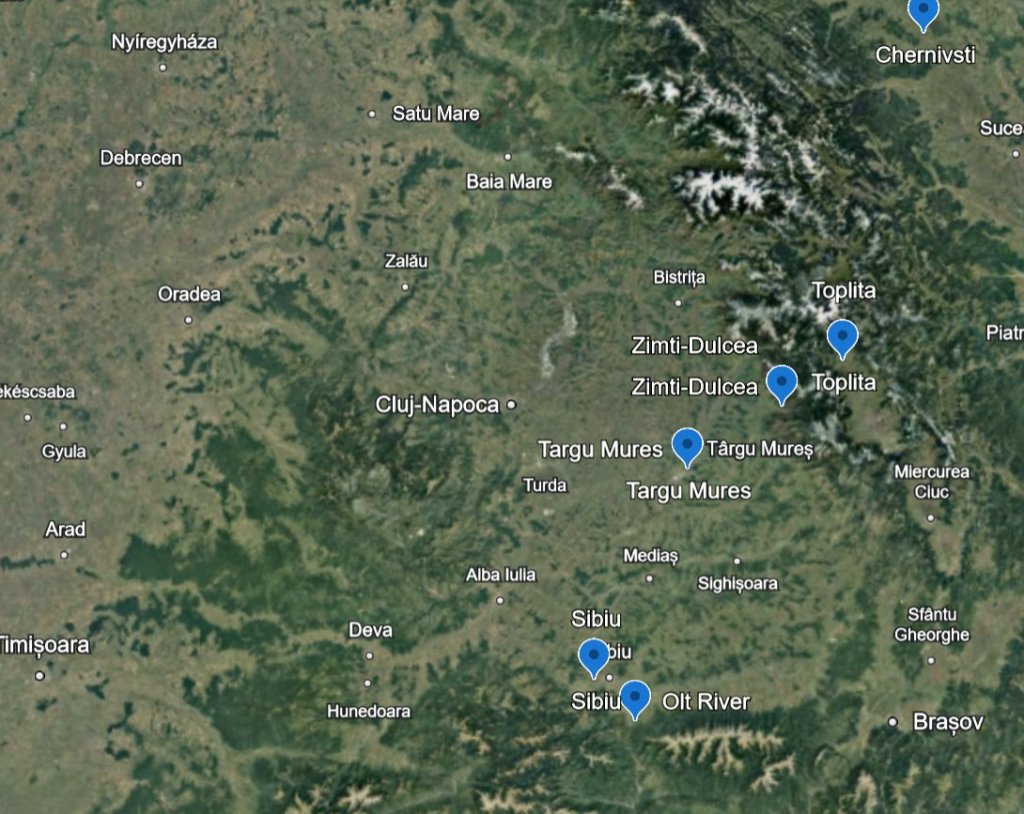

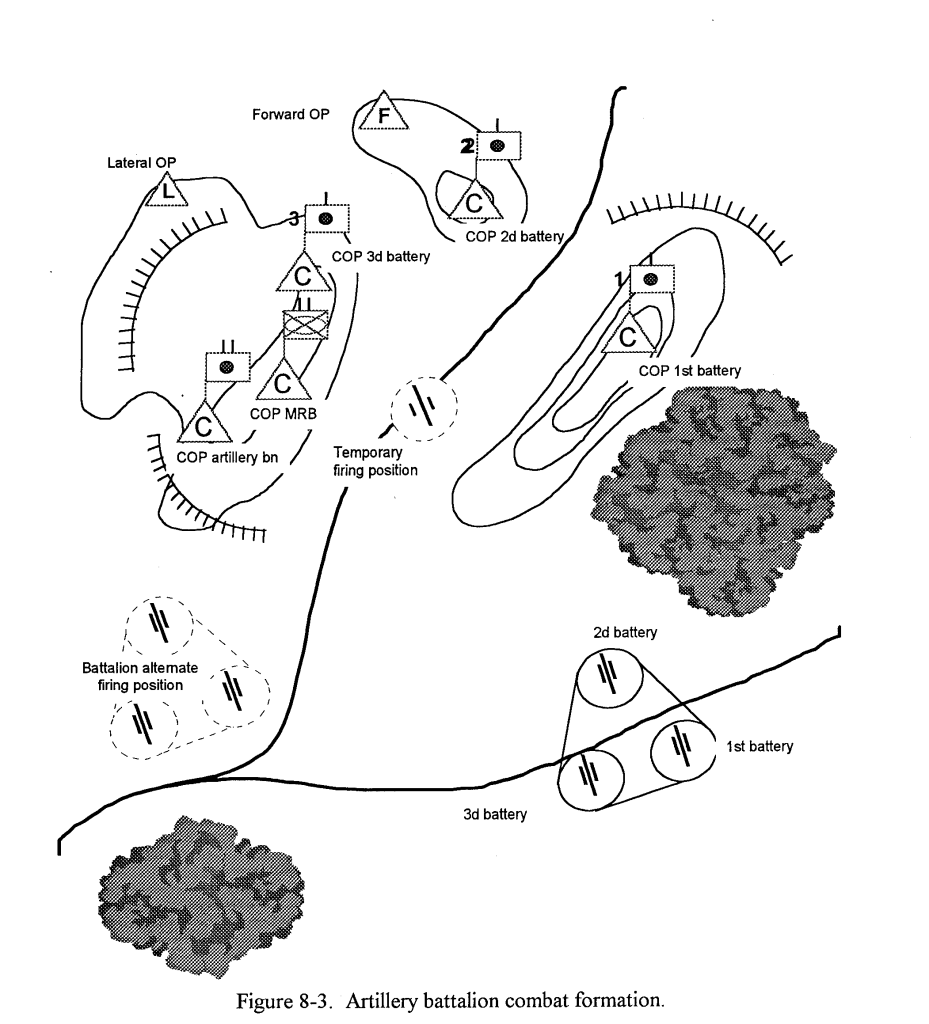

An excerpt from an in-universe book by “Kestrel Publishing” (any military history fan will know who this is a reference to) on the gear of the Soviet-Romanian War in All Union. I spent way too much time and had way too much fun making this.

From “Uniforms and Equipment of the Soviet-Romanian War” by Kestrel Publishing

Fig 1. Yefreiter (Corporal), 17th Mobile Corps, Dniester Front

-This representative mechanized infantryman wears uniforms and gear typical of the most advanced mobile corps. He has a low visibility unit patch depicting the phoenix/”Huma Bird” that served as the 17th’s symbol over his PKU-94 army uniform set, which served as the newest uniform set in the army. He also wears a heavy (over 30 pounds) 6B4 ballistic armor vest and the newest UBS-1 helmet.

Gear:

The man depicted in figure 1 is representative of most mobile corps BMP/BMPM infantryman. As a result, he carries a 5.45mm AK-74, still the standard infantry weapon among mobile corps as it would cost too much to fix what wasn’t broken. The soldier also has several grenades, a medical kit, and a pair of NPDS-‘YUKON’ night vision devices (helmet mounted and rifle-mountable handheld). Also of note is the MV-9 rifle grenade in a leg pouch. Similar to the Spanish FTV series, these rifle grenades use a “bullet trap” system where a live round can be fired to trigger them without issue. With a theoretical 150 meter range.

Camouflage:

The 6B4 vest is plain green, while the PKU-94 uniform is colored in the large-spotted “Gumdrop” camouflage worn by mobile corps soldiers.

Notes: 6B4 vests were available in large numbers and were proven to be durable, but were also very heavy. They were the most common mobile corps infantry outfits among BMP troops who spent most of their time in vehicles. MV-9 rifle grenades were an awkward experiment, many viewing them as more trouble than worth given that proper underbarrel launchers, LAWs, and full-size RPGs (to say nothing of vehicles and artillery) were not in short supply. More modern and efficient armored vests were used by mobile corps, but were more limited in supply.

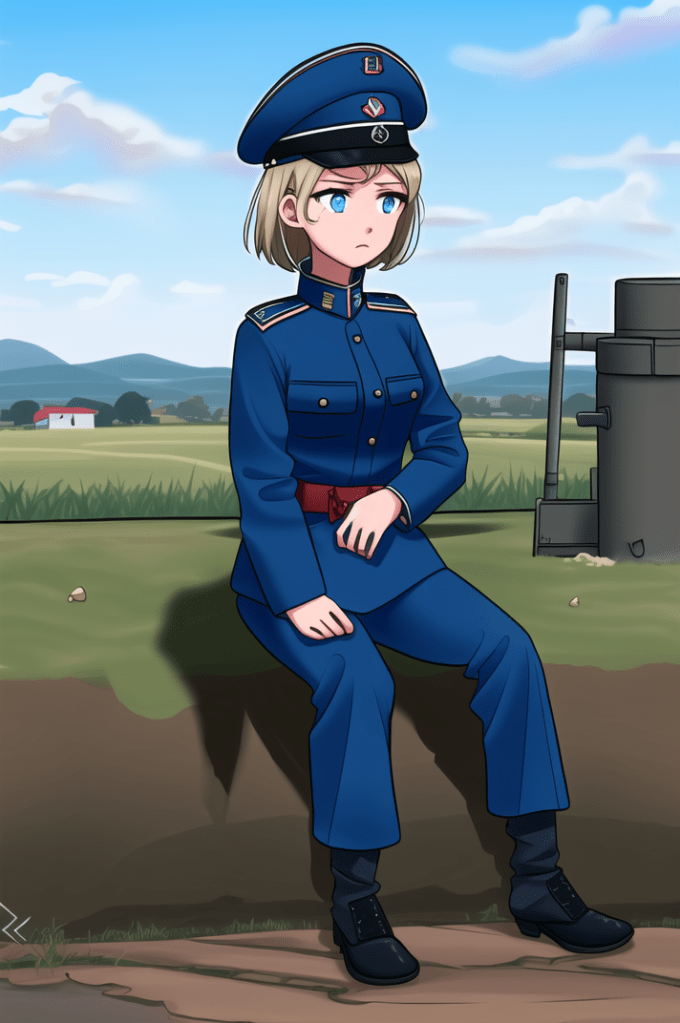

Fig 2. Junior Sergeant, Tank Crewman, 64th Mobile Corps, Dniester Front

-This representative mobile corps tank crewman wears a coverall in “Gumdrop” camo and an internal microphone variant of the UBS-1 helmet (which was meant to be usable by infantry, law enforcement, and vehicle crews alike, starting off as one of the famous ‘face shield helmets’ similar to the Altyn/K63 before being adapted).

Gear: The figure depicted carries an A-91 bullpup PDW in a slung scabbard, a weapon commonly issued to mobile corps vehicle crews. He also has a classic Makarov pistol in a shoulder holster.

Fig 3: Spetsnaz recon troop, 48th SPF Brigade

-This spetsnaz operator is dressed in a “Gorka” canvas suit popularized in Afghanistan, and wearing a similar chest rig. He notably does not have a helmet, instead wearing a bandana/durag and night vision goggle rig.

Gear:

The man in Figure 3 carries a suppressed AK-74 along with the gear for a long-range recon patrol mission (which explains the lack of armor). He wears a Taiwanese-made version of the American PVS-7 night vision goggle system. These more advanced night vision devices (either imported or domestically built) were reserved for the likes of recon, special forces, lighter infantry, and anyone not bound to operate in close proximity to a vehicluar sight. Even in mobiles, regular infantrymen usually kept only the Gen I “YUKON”.

Camouflage:

The Gorka Suit and bandana is in KLMK-Berezka, an existing minimalist but effective camo pattern used for decades in the USSR.

Fig 4: Motor Rifleman, 87th Motor Rifle Division

-This man from a legacy division wears the classic plain khaki Obr88 “Afghanka” and a similarly Cold War vintage SSh-68 helmet. His load bearing equipment is a belt and “Chicom” chest rig, a classic easy to build or obtain type.

Gear: The man in Figure 4 is equipped almost identically to the average man on the eastern side of the Fulda Gap. An AK-74 5.45mm rifle, a basic steel helmet, and nothing an American of the 80s wouldn’t find familiar.

Camouflage: Legacy divisions had not (yet) adopted camouflage as standard issue. However, helmet covers from large fabric tarpaulins and the like were frequently made, as is the case here.

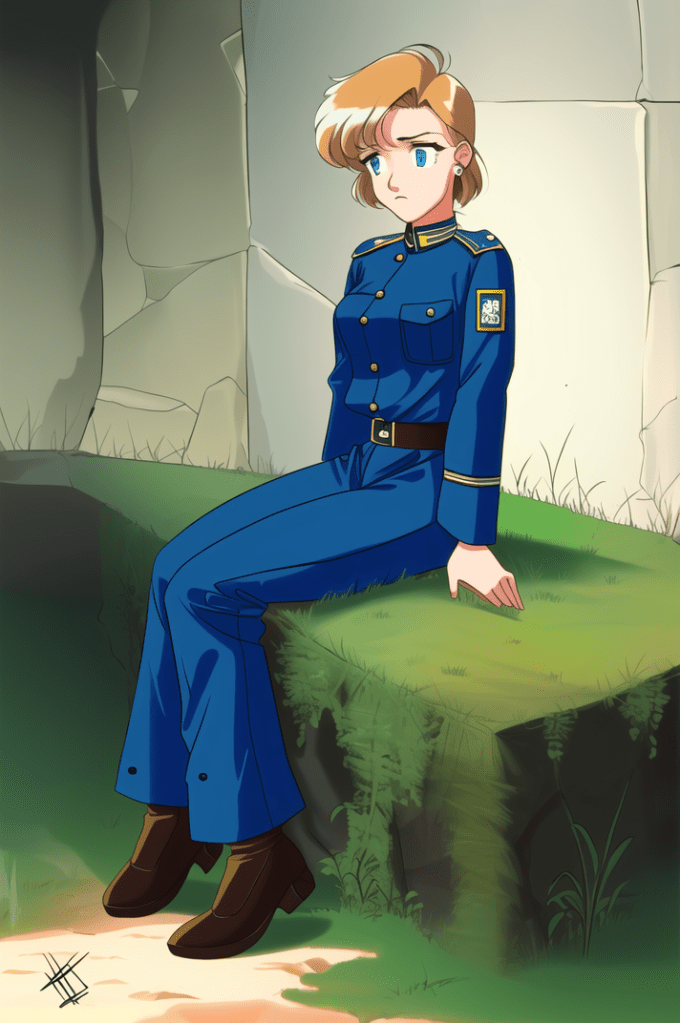

Fig 5: Infantryman, Bulgarian 1st MRD

-One of the higher-equipped Bulgarian formations. He is dressed similarly to a man from a legacy motor rifle division, but his items are of a particularly Bulgarian quality.

Gear: The man has a Bulgarian Arsenal AR, a locally built version of the 7.62x39mm AK-47 which was the general Bulgarian standard issue item. He wears a large “slick” plate carrier (Bulgaria’s prewar army had adopted such things) and has a more modern-looking “Mayflower” chest rig over it, both licensed for production in Bulgaria starting in the late 1980s. His helmet is the slightly different shaped Bulgarian M51/73.

Camouflage: Bulgaria, unlike the USSR, had by this time had a splinter-type camouflage pattern as standard issue for its standing army, and it is shown in the gear depicted in the picture.

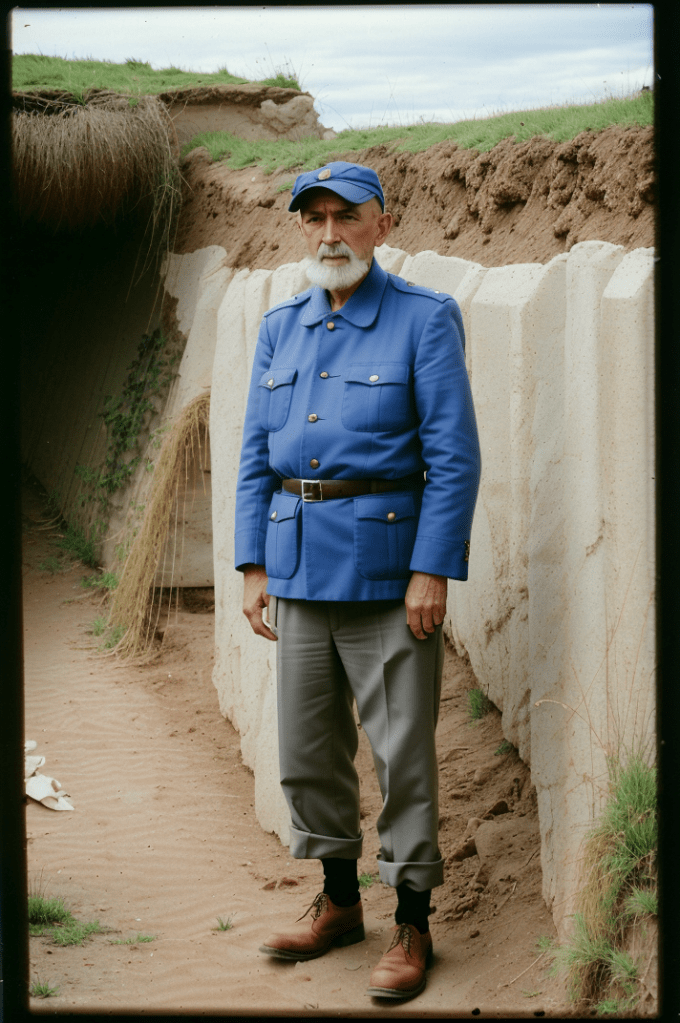

Fig 6: Infantryman, Bulgarian 10th Infantry Division (Mobilization)

-This older man stuck in a ‘deep mobilization’ infantry unit is a double anachronism. His uniform is an M15 Bulgarian uniform from World War ONE, along with the green-with-red-stripe peaked cap from the time period and a set of civilian shoes he provided himself. A Bulgarian Chicom-style chest rig serves as the only sign from a distance this is not a reenactor.

Gear: The infantryman has an old surplus AK-47 as his main armament and little else. Most is personally obtained and inadequate. Bulgarian low-tier mobilized infantry like this would have a ratio of around 7 AKs, 2 SKSes, and one Nagant per ten soldiers, varying up and down a little. The smarter officers would give long rifles as designated marksman weapons to their best shots.

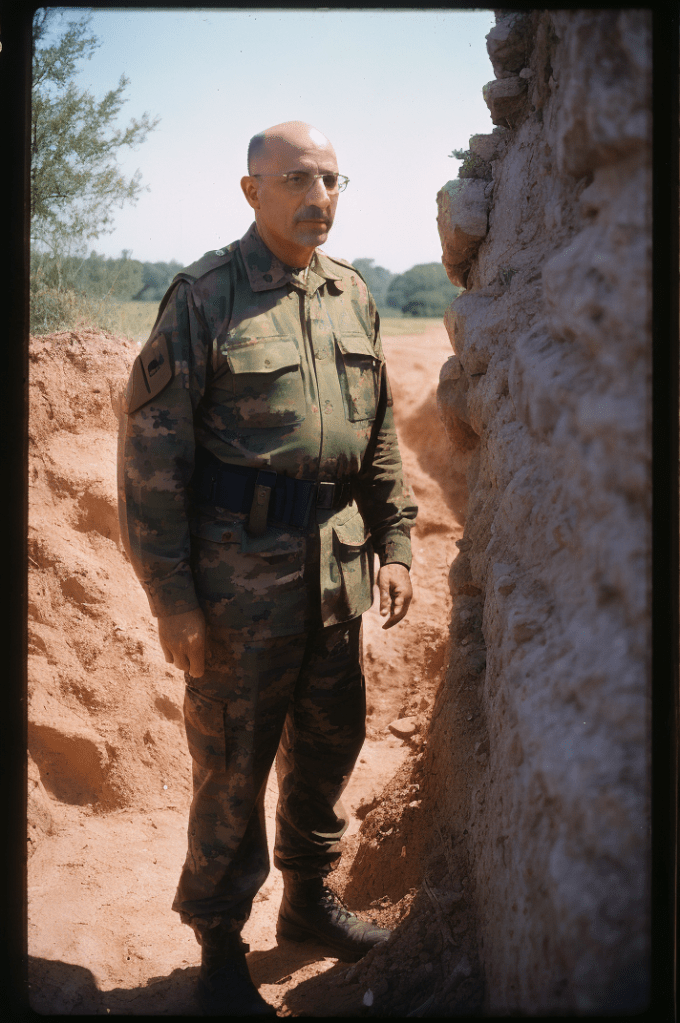

Fig 7: Soldier, Romanian Army, 2nd MRD

-The average Romanian soldier was dressed like a Soviet soldier from thirty years earlier and armed like one, and this representative man from the prewar standing 2nd MRD shows it clearly.

-Gear: This man wields an AK with the famous Romanian wood foregrip. His Romanian M73 helmet ironically was introduced in the 1970s to distinguish Romanians from other Warsaw Pact armies.

Fig 8: Mechanized infantryman, Romanian Army, 5th TD

-This Romanian infantryman wore what was called the “Persian Outfit”, a reference to gear made in one of its few remaining allies, Iran, and given to a luckier few Romanian units. His outfit looks more western, a reference to their continued production of American-style equipment first imported in the shah era.

-Gear: This man in a ‘Persian battalion’ carries an Iranian-made AR-15 platform rifle in 7.62x39mm, and wears a helmet with the outer shell of a WW2 American M1 yet with kevlar inserts to add to it. His load bearing equipment could have been straight from the Iran-Iraq War.

Camouflage: The camo is a brushstroke pattern with red, black, and green stripes on a tan backdrop, used frequently by Iran and with a similar color to various Swiss and German patterns. Similarly better-equipped “Chinese battalions” had MAK-90 AKs with distinctive large wooden stocks, Chinese GK80 helmets, and camo in the green-dominant pattern of that country (which was frequently more suited to Southeast Asian jungles than Europe in early autumn).

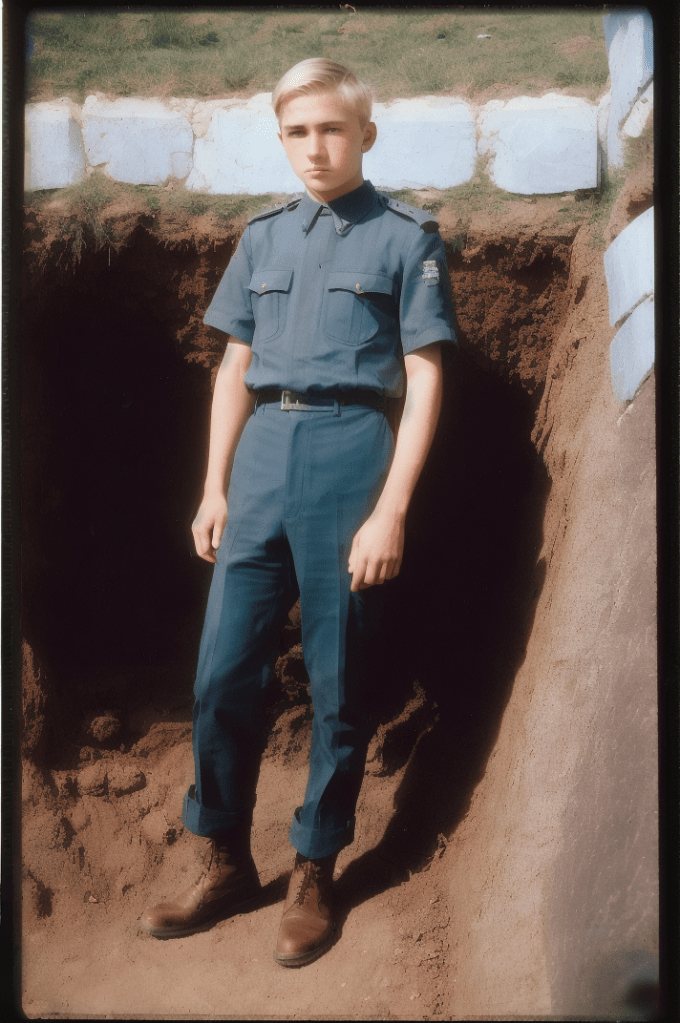

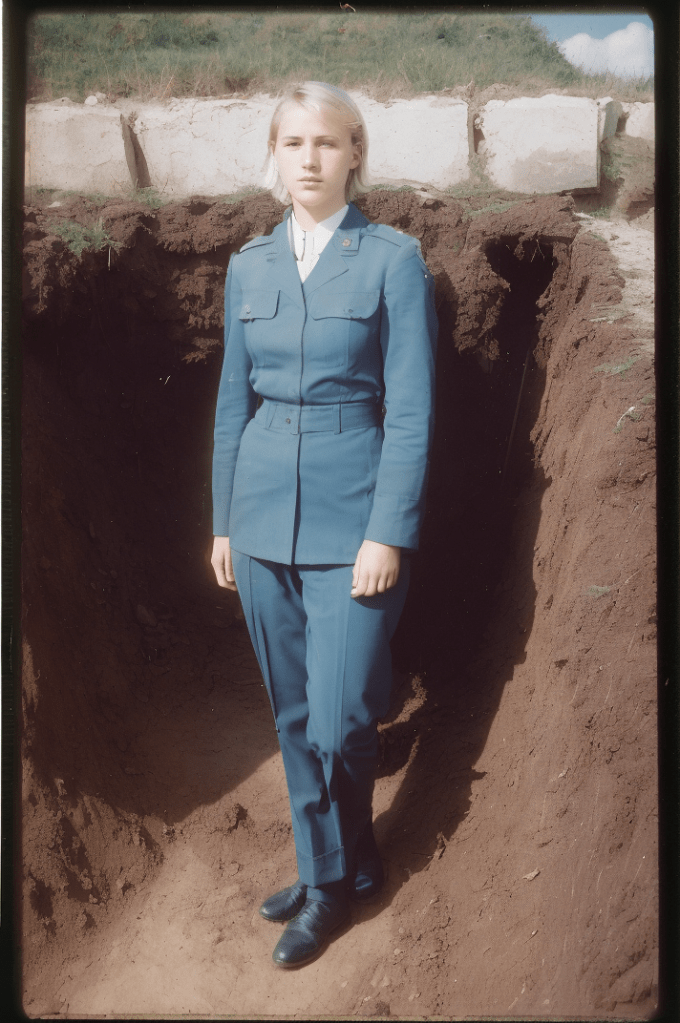

Fig 9: Romanian Patriotic Guards, Independent Brigade

-The Patriotic Guards were the mass mobilized, bottom-barrel desperation Romanian infantry. They had a distinct uniform built up over decades that meant it could satisfy even the large call-up. A soft blue harking back to the World Wars, this color makes the Soviet-Romanian War the final war as of this book with a mass-produced, standard issue blue uniform for ground troops.

-Gear: This Patriotic Guardsman carries a World War II surplus VZ-24 Mauser Rifle and gear of similar standards. Such desperation measures were not uncommon, as were the effectively homemade grenades and explosive charges. He wears a blue cap. Often such formations would have something like a similar vintage and same caliber ZB-53 tripod machine gun as their primarily (or, to be blunt, often only) heavy weapon.